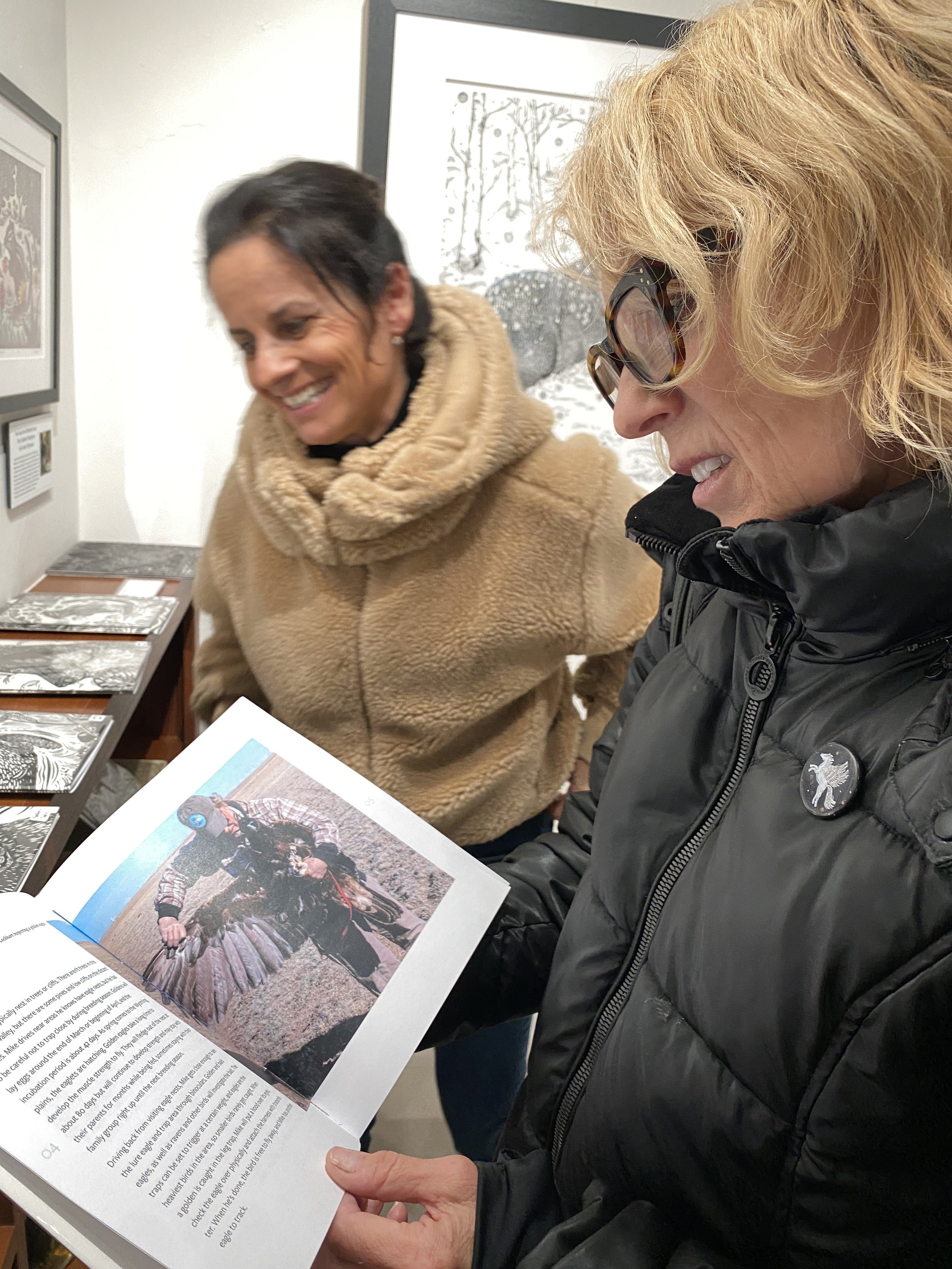

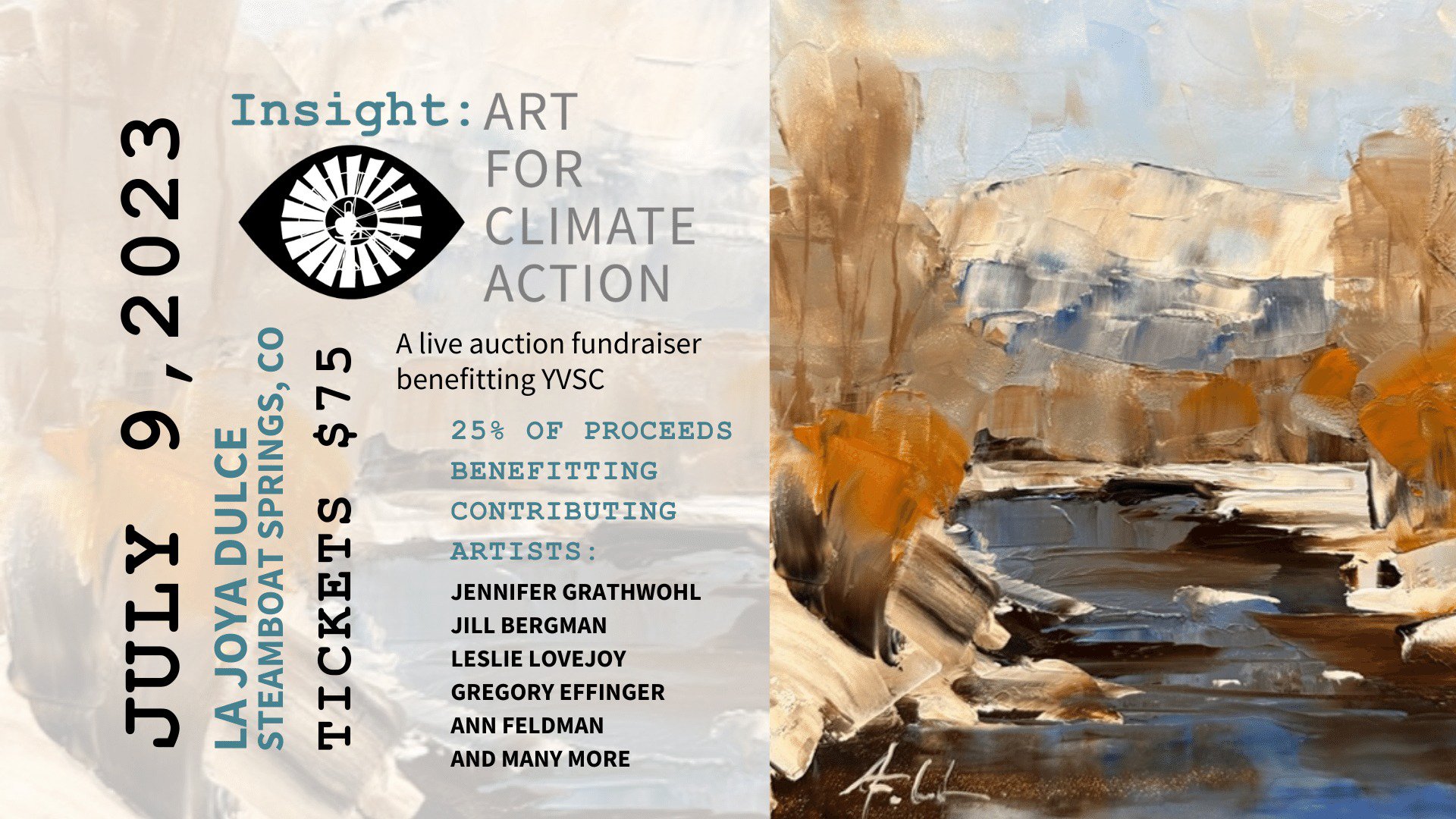

I am thrilled to be a participating artist, and also have been able to help plan Insight: Art for Climate Action, an event and fundraiser for the Yampa Valley Sustainability Council. We encouraged submitting artists to create work in one of their priority areas, resilient land and water, waste diversion, or energy and transportation. Below is my artist statement sharing thoughts about the area I chose to work in, as well as a poem about monarch butterflies.

If you are in the Steamboat Springs area, please come to the Insight event on July 9 at La Joya Dulce, there will fantastic artwork and lots of fun! Find all of the details on YVSC’s website.

Monarch Migration, linocut assemblage by Jill Bergman created for Insight: Art for Climate Action

As a young person in the 1970’s, I developed climate anxiety, something that didn’t even have a name until recently. My parents are scientists, and engaged with environmental issues. There was talk at home about water and air pollution, pesticides, and the hole in the ozone layer. I cared so much, but felt unable to act. For decades I tried to ignore these scary issues, but I was sad and worried about what humans were doing to the planet. When I began to take action to engage with these problems instead of avoiding them, I tried to find ways to use my talents in the areas of conserving wildlife and natural landscapes. There are countless things to be done, but the bigger picture always returns to fighting climate change. Without green energy and a shift to respecting nature and the interdependency of life, we will only cause damage to wildlife, wild landscapes, and everything else including ourselves.

I’ve learned the way to fight climate anxiety is to get involved with fighting climate change, but I still have sad days. Last summer when the International Union for Conservation of Nature placed the migratory monarch butterfly on their Red List as endangered, I cried. Monarchs are strikingly beautiful, have an unbelievable migration story, and aren’t polarizing or harmful. But through our misguided policies and lack of awareness, they are in trouble because of habitat loss, pesticides, temperature extremes triggering migration before milkweed is available, and other issues linked to climate change. Even with these challenges, Emily Spencer, Natural Resource Specialist at Dinosaur National Monument who participates in tagging the butterflies, says monarchs are “smart, resilient survivors and surprise us in so many ways.” Citizen science is helping find new areas where monarchs overwinter inland and in smaller groups. There is still much to learn. Connecting pollinator habitats, stopping deforestation, and lowering greenhouse gasses will help the monarchs, but also help all of the rest of us inhabitants of the globe. There are countless ways to get involved!

Monarch Garland, 8’ long string of hand-printed paper butterflies

For the 3D assemblage I created, Monarch Migration, also the paper Monarch Garlands, and in my artwork in general, I wanted to focus more on using existing materials, reducing waste and buying less. If we can raise awareness on this issue, this will help reduce greenhouse gasses through lessened production of materials, less shipping, and keeping things out of the landfill. With printmaking I always have test prints and some that don’t work out. I save them. I also have not-favorite inks from the past, or materials that were given to me. As a picture framer, I have scraps of mat board, and frames that can be reused. Every part of the monarch work created for Insight (except the framing glass and clear plastic wire) was made from things that I could have considered trash, but chose to reuse. I’m excited to continue down this path.

Monarchs printed on Rives BFK printmaking paper, on the back and obscuring former reject prints.

Monarch

by Jill Bergman

In the garden like an extra flower,

the flash and slow wink of luminous orange, big as my palm,

a monarch sits resting in the afternoon sun.

Now heading crookedly through the breeze and sweet blooms,

on a mission, going places,

though you’d never know from looking.

How can this flutter-by travel 100 miles in a day,

going to a gathering place it’s never been before?

It’s astounding, and completely preposterous.

These days they are counted and tracked.

But how could you ever count something so light and uncontained?

Are they counted by little girls with butterfly nets?

Are they tracked by mountain men

who read tiny butterfly footprints on a milkweed leaf?

No, they are tracked by scientists and volunteers with stickers.

Net a butterfly, put a number on the wing,

and hope someone down the line will see it,

like a message in a bottle.

In their travels, are the monarchs guided by the sun’s angle,

or UV light, or the earth’s magnetism, or hocus pocus?

Are they guided by love?

Do they look forward to their winter gathering like a festive family reunion,

snuggling together on Monterey pines greeting long lost cousins?

We don’t know how they do it, but memory didn’t guide this migration.

The butterfly in my garden only lives a few weeks.

Her grandchildren in the fall will feel the bite of cold and head south or west,

living months longer while fasting, and battling winter storms.

Spring sends them fluttering like joy, to lay tiny eggs in milkweed nurseries.

Eventually, their grandchildren will reach my Colorado garden.

Go with blessings, carry our hope.

The world is hard, and we only make it harder for the delicate and powerless.

It feels terrible to be a member of the species

making this planet inhospitable for monarchs, and ourselves too,

causing heat waves, drought, and extinctions.

I’d like to be a member of the species who can change for the better,

who can stop making bad decisions.

I’d rather be guided by love.